Unplayable games and untellable tales

A sort of review of The Terraformers by Annalee Newitz

by

If you're here for a normal kind of book review, the kind that says, should I read this book? Is it good? The answer is yes. It has a sentient moose that communicates by text messages. I don't know what more you really need to know to decide to read the book. Go read the blurb on the back, then go read the book, and then come back and read my blog post.

OK, you've done that? Then come with me on a journey where I talk about what an imaginary game inside The Terraformers told me about the kind of story The Terraformers tries to tell, and why it's so hard to tell that kind of story.

"Make this cat moose brown." -- The Terraformers

"Make this cat moose brown." -- The Terraformers

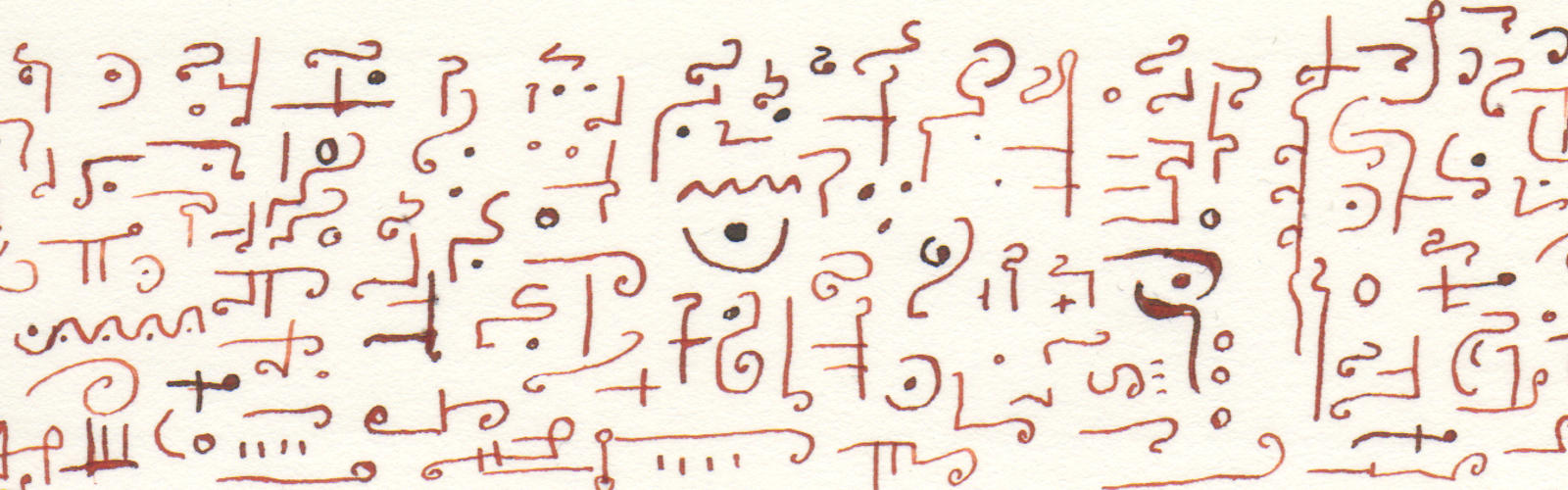

Let's start in the middle, or actually, the middle of the last third of the book. Moose, a sentient cat reporter, and their friend Scrubjay, a train temporarily in the guise of a robot beaver, go to a demo night for indie video games at a club in the robot cruising district. Like most trains, Scrubjay loves games and eagerly tries out one of the demo games, Farm Revolutions.

Unplayable game #

The farm revolution is an important historical event as well as a foundational myth of the book's multi-planetary, multi-species, hybrid biological and robotic society. It's how humanity saved itself, and the earth, and how we ended up in this state of affairs where Homo sapiens are just one of the many kinds of people around (and in fact what they call Homo sapiens is hardly recognizable to us except in the most outward way). It was a time of heroes, and tricksters, and battles and amazing inventions–or so Scrubjay thinks until they start trying to play the very historically accurate game. It turns out the heroes that Scrubjay knew about left little historical trace, their famous speeches are reconstructions from centuries later, and the game sucks because it's not clear what you're supposed to do, or how to gain experience–never mind win. The game designer wants to help people understand the real history and to help them understand that revolutions aren't one-time events with heroes fighting an epic battle, and it's not even clear when they start or end. That's fine and good, Scrubjay and Moose say, but the game is unplayable.

I think that the game Farm Revolutions is a hint, or maybe a big flashing sign, from the author about the kind of tale they are trying to tell with The Terraformers. Which is to say, they’re trying to tell the story of what revolution looks like beyond the mythologized moments of glorious battle. The Terraformers tells the whole story of politics and ecosystems and struggles for personhood, not just the exciting parts that are fun and easy to tell. And, by including the game they’re also dropping the hint that they know telling this kind of story is risky and could go wrong.

Untellable tale in three parts #

The Terraformers starts out with a fairly conventional structure. The first third of the book would make a fantastic stand-alone novella, in fact. We follow Destry (close enough to our kind of human to make the ways she’s different from normal humans stand out) and her work partner and mount, Whistle, the aforementioned sentient moose who texts. Within a few pages, Destry shoots and kills a jerk who is ruining the ecosystem of the planet that she is helping to terraform. She has a clear antagonist in the form of her evil boss Ronnie, who only turns out to be more of a jerk as the story goes on. There are romances, mysteries, intrigues, an epic battle, and a bittersweet victory. It’s great.

Then it’s 700 years later, and Sulfur, our main point of view character thinks of Destry as a historical person who was kind of a jerk for signing an agreement with the corporation that owns the planet–the very agreement that let Sulfur’s people maintain independence while participating in the planetary society. What? I thought Sulfur was kind of a jerk or maybe even an idiot kid, even if they were centuries old. But of course, from Sulfur’s point of view, Destry’s hard-won victory and the treaty she sacrificed so much to secure is now the unsatisfying status quo. Sulfur wants more freedom than the generation before dared dream of. Hey friends, it’s the Hegelian dialectic, that’s how it goes.

This middle third of the book is mostly a slow-paced fact finding mission where Sulfur (a hominid but not a Homo sapiens) works with Destry’s successor and two other people to survey the planet, which now has cities, and figure out what kind of public transit system they should establish.

After the exciting first third with Destry and Whistle with moose romance and battles and volcano mysteries, it was kind of a let down. Oh sure, we see how the planet has changed in just 700 years, and there’s all the hilarious and sexy events at The Tongue Forks, which is the best multi-species burlesque bar I’ve ever read about, but where are the heroes? Where are the battles? The most important thing that happens in the section is getting our new corporate villain to agree to a public transit system proposal for sentient flying trains, which happens almost entirely off the page.

And then finally, it’s almost a thousand years after that and one of the protagonists now is a sentient train, oh hey it’s the train we saw born at the very end of the last section. The planet is almost unrecognizable from the first section, and the struggles of the people who came before give rise to the struggles of the current bunch. Now, finally, the forces they fight against are a lot more complex and nebulous. It’s no longer just a single antagonist, like in the first section, or a hated treaty and a handful of corporate honchos. Now, the antagonist (if we can even call it that) is a whole system of corporate planetary ownership, interplanetary law, personhood status, and complex alliances. Former enemies become temporary allies. Friends split into factions that have to find common ground or compromise and forgiveness. Society has got a whole lot more complicated.

In the end, even the victory is somewhat tentative, and political, and having seen how it started with the treaty from the first section, you have to wonder, would some future people of this imagined world also look back at this hard-won political victory and think it’s an odious status quo? And, I think, we are meant to think that of course they would. There is no final victory, no moment when the Farm Revolution, or any emancipatory movement is finished. That isn’t bad, or sad. Each improbable victory lets them (lets us) imagine the next possibility.

Fiction as speculation about possible futures #

This kind of story is hard to tell in fiction. Even science fiction, which is supposed to be the fiction of ideas, usually sticks to more conventional story structures. Like the game Farm Revolutions, a story about a historical movement and systemic change risks becoming unreadable. Not a lot of writers manage to pull it off, and I think you need, in some ways, to trick your readers into it. The last book I read that attempted something similar was Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry for the Future. Of course, a book about terraforming invites comparisons to KSR’s Mars trilogy, too, which also features stories about systems and revolution. KSR’s books keep me reading even when plot goes out the window (or is, I don’t know, set aside for other considerations) because I love his descriptions of environments and his superb characters.

In The Terraformers, Newitz never quite lets the plot go as slack as KSR does in, say, Ministry for the Future. But they do deploy some tactics that make up for the occasional lack of straightforward struggle that would drive a plot forward.

The way the “facts” of the world building unfold before us as readers are a kind of action. I think this is where Newitz’s experience as a nonfiction writer gives them an advantage. The Terraformers is full of revelations that build on each other, some fun, some funny, some surprising, and some shocking.

Next, and I cannot overstate this, The Terraformers is really funny. There are just lots of hilarious lines, absurd situations, and wonderfully weird and obviously intentionally funny bits of worldbuilding. Including the Farm Revolutions subplot indicates to me that Newitz is well aware of the ways The Terraformers might be received as a novel, and even that is part of their authorial strategy of deploying humor.

It’s also funny about sex while being actually sexy. I alluded earlier to the scene in The Tongue Forks. Not only do sentient cats have funny things to say about what humans find sexy:

Sulfur picked up a local public text from the cat in the next booth: It’s not just dancing—it’s some kind of sex thing. Humans are obsessed with it. I can’t figure it out, but I don’t mind watching, you know? One of the other cats sent back: Those are excellent stretches. But how is that sexual?

There is also an actual sexy encounter between a humanoid-robot hybrid and our hominid protagonist which maybe I won’t describe in detail, but it’s somehow both funny and sexy, and becomes even more so when in the last third of the book we learn about, as the chapter title says “the robot kinksters of La Ronge.”

There's probably many other ways to tell an untellable tale, but worldbuilidng, humor, and sexiness work pretty well for The Terraformers.

Disclosure: I know Annalee Newitz socially, so it might make me like their book more than if we were complete strangers.