Logocentrism again?

You might think that words mean things, but what if the things aren’t there

by

I thought I had a good handle on “logocentrism.” Then I read a post that used it to mean something completely different than I had understood it, and so I started to doubt myself. I made it worse by asking ChatGPT about logocentrism. It gave me a mix of grossly misunderstood Derrida, general waffle, and lies, which made me think that maybe I can’t trust what anyone else says about logocentrism on the internet, at least nobody non-academic (and even then), and I had better go back to the text again to figure it out. It's my one weird trick in life that’s served me well. Go back and read the damn thing yourself. Whether that thing is obtuse critical theory, a legal contract, an academic theory, or the damn source code even if I don’t know the language.

Really, I wanted to write part 2 of Dangerous texts: Vajrayana practice texts, technical manuals, and your annual review, and talk about logocentrism and Vajrayana transmission and the way literal magic makes the metaphysical ideas about presence and the voice relatively easy to decipher as compared to the metaphorical way they hide out in other texts. But to do that I have to feel pretty sure I have a reasonable grasp of what logocentrism is and I’m afraid I no longer do.

Previously #

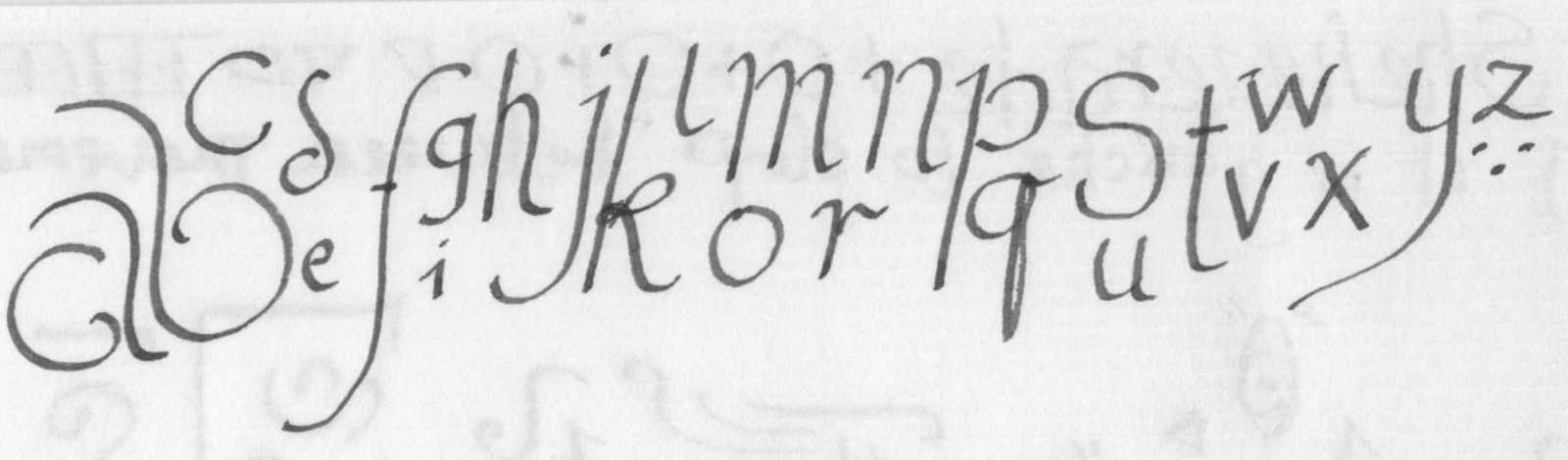

To review, I first glibly defined logocentrism as “mostly a weird way of saying European imperialism, cultural and otherwise.” Then, I refined that definition in the next post: “Logocentrism is the idea that the spoken word is primary–both as in the first and most important–form of language, and the written word is secondary.”

But this other blog post, which to be fair, I read through Google translate, seemed to use “logocentrism” to mean privileging reason, science, and like, discursive thought. I don’t quite remember and I’m very tired so I’m not going to look it up because I don’t know how I even found it. I think it’s important though, this interpretation, or perhaps misinterpretation–I don’t know which of us is wrong here–of the logos in logocentrism as having to do with logic and formal reason.

Then again, the somewhat helpful Wikipedia entry for logocentrism says:

“It refers to the tradition of Western science and philosophy that regards words and language as a fundamental expression of an external reality. It holds the logos as epistemologically superior and that there is an original, irreducible object which the logos represent. According to logocentrism, the logos is the ideal representation of the Platonic ideal.”

Wait what? That first sentence makes sense but then we’re just back to circular definitions. I hate it.

I must say (metaphorically, actually, I only write this) that if a person ever needed proof that signifiers and signifieds have become unmoored, and you might as well through the whole Sign in the garbage and get a new one at the store, this process of hunting down what logocentrism even is sure is a compelling bit of evidence. I’m not even trying to figure out one of the hard ideas like “différance” or “trace.”

It's probably all Plato's fault #

I can sort of stitch all this together, though I don’t know if “this” is logocentrism. Here’s the chain of ideas, roughly:

First, assume there is some knowable reality. (You probably go around doing that most days, out of convenience, as do we all.) Second, assume that you can point at that reality. Third, assume that the words we speak point to real things.

So, words mean things. A commonplace which, uh, maybe isn’t so true, not so directly.

Next, we get to the part I wrote about previously. Spoken words are sounds that point at real things. Written words are visual representations of sounds. So written words are the visual representation of sounds that point at real things. Or that, at least, is the whole chain of logocentric reasoning, which Derrida is against. And, not so much “against” as he argues that it’s not really true, and that it’s very interesting how everyone seems to be convinced it’s true.

The weird part #

I haven’t even got to the weird part yet, because I was just trying to get the straightforward meaning. Somehow reading secondary texts has made it all worse, not better. Except for Judith Butler’s introduction to the 2016 Spivak translation of Of Grammatology–that’s good.

The weird part, and Butler’s intro really draws it out, is the bizarro leap that Derrida makes between the idea that if written words are not the representation of the sound of speech, then writing does not conjure the presence of the speaker, which means that there is no speaker who can make things real by speaking their names in imitation of God, which means that words do not point to a real thing, which means there is no real thing. That is, there is no “presence,” though if you thought the journey to figure out what “logocentrism” meant was dense, maybe go take a bathroom break when I write about “presence,” as I will. (Actually, don’t because that part will also be about poetry)

For my practical purposes as a poet, I think what all this means is that Derrida argued that the feeling you have of a sense of the thing before you write the words is just a retroactive illusion created by writing the words, and that the presence of meaning before words is not really there. I guess I could be wrong about my own experience of the world, but I’m pretty sure that this is bullshit. Having both experienced meaning and presence during long periods of wordless meditation and literal aphasia, I know presence and meaning exist without words. Second, and possibly more important, I know it is possible for words, as in poetry, to evoke, and I do mean evoke like magic, that sense of presence.

I agree that words don’t just point at real things (or real idea things) but also generate meaning from the play of signification. That is, the meanings of words arise out of their use among other words, changing meanings in context, potentially shifting completely from what they pointed at before. But just because words are wiggly doesn’t mean there are no things or ideas that exist before words. That’s my big fight with Derrida.

It is possible, and I keep saying this, that I am wrong. It’s possible that I’m wrong about what Derrida claims. It’s possible that I’m wrong about my own experience of the world. More, as I also keep saying, next time.