What's a hero?

by

In her introduction to the The Odyssey, translator Emily Wilson examines Odysseus' status as a hero. In the narrative, one of his interlocutors ask Odysseus if he's a pirate, which he denies although he doesn't deny the violent and treacherous acts attributed to him. What it meant to be a hero was rather different in Homer's Greece than in our time. Wilson writes:

"Being a "hero," heros which in archaic Greek does suggests a warrior and does not imply virtue--is different from being a "pirate" in that it is a much more positive term, which a man can apply to himself; nobody in Homer admits to being a pirate. Like pirates, warriors sack towns and and kill the inhabitants; the main difference is scale. Odysseus goes on to infiltrate the enemy's dwelling, maim him, and poach his beloved sheep, the wealth of his household--an act that is clearly analogous to the hero's previous triumph over the Trojans."[1]

Not long after reading Wilson's introduction, I was listening to a podcast about the works of science fiction author Gene Wolfe where the hosts talked about how deeply flawed one of Wolfe's heroes was[2], wandering around and getting lost at sea, cheating on his wife, starting wars, betraying people who depend on him, and not even getting that much done. He wasn't a classic hero like Odysseus and his dubious quest was no epic like the Odyssey, they said. Maybe they were making a subtle joke. Because if you want a hero who is Problematic and whose quest is more of a straggle home that mostly fails and gets everyone around him killed that is literally Odysseus.

Somehow two contradictory ideas are lodged in the popular imagination: that ancient epic heroes like Odysseus are epitomes of real heroes and that real heroes are not only brave and accomplished but also morally good. But if you read the ancient epic tales the heroes are pretty weird.

Good or good at #

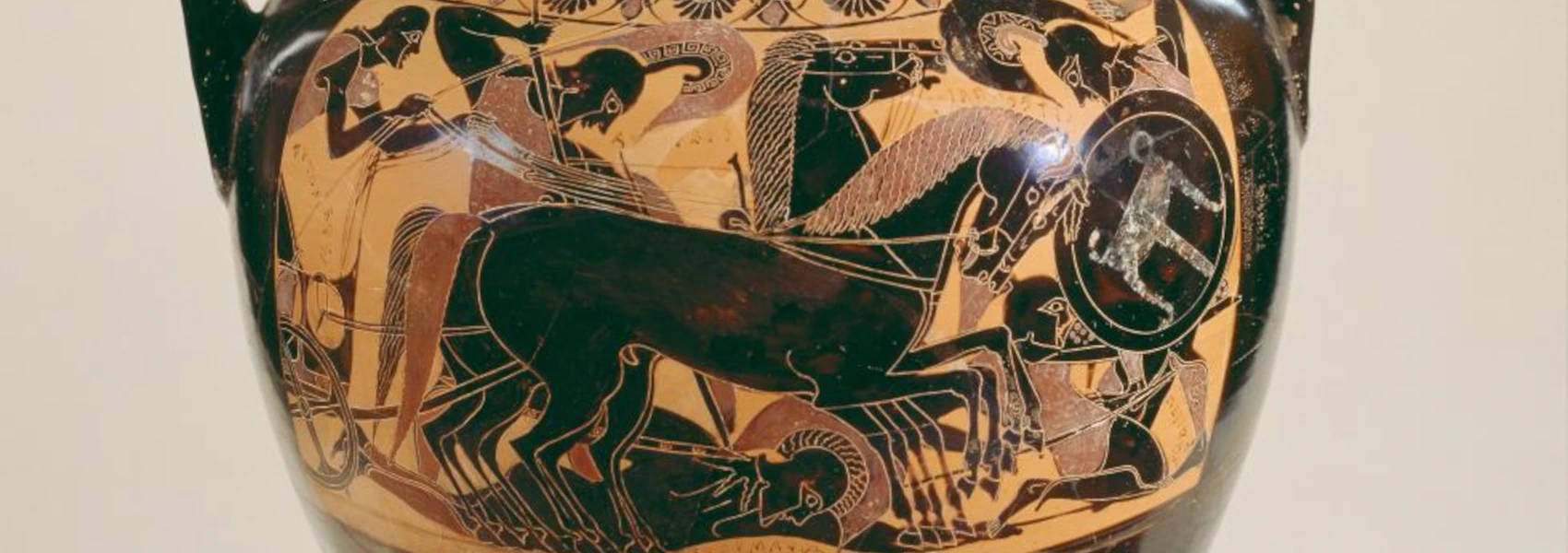

The ancient heroes aren't good guys. They are guys who are good at doing things. There's another neat ancient Greek word for that, arete. Of course it means a lot of different things over time, and Aristotle, obnoxious moral philosopher that he is, even has a whole chart[3] about it. It gets translated as "virtue" in some contexts. But arete is more like excellence, and anything or anyone can be excellent in its own way, or in a particular way, without being all around good. You might be an excellent archer or excellent poet or an excellent vase while still being a complete shitheel of a person in other ways. Well, not the vase. The vase probably did no wrong, even though it might depict something pretty violent and possibly quite wrong, like the vase I used as the header, which shows Achilles trampling a dude in battle and then getting off his horse to kill him once he's down.

It's satisfying watch competent people do what they're good at. At the same time, I think it's tempting to attribute other forms of goodness to the competent. If Achilles is such a great archer, surely he must also be brave, and maybe also kind, and honest, and patient.

Hero, protagonist, and anti-hero #

I don't know when a hero started having to be morally good. Certainly by the time Plato was writing, he objected to shady Odysseus and even decided to kick poets out of the Republic for, among other things, telling such immoral tales. The neoplatonist Porphyry tried to retcon some of the more sacrilegious Homeric tales by insisting they be interpreted metaphorically. However, the first place I've noticed the swing towards moral and moralizing heroes is Le Morte d'Arthur where about two thirds through the tales it's suddenly not OK to murder people in duels, seduce other guys' wives, or even just have sex at all.

Yet, people still want stories about heroes more like in Homer than in medieval morality tales. Morals change and anyway isn't it more fun to read or watch movies about people who do big, interesting things and are a little, or even a lot, bad? From the hero who is good and good at stuff, we move to complicated protagonists again and then even further, straight up anti-heroes, the literal villains from earlier stories brought back for their own main story line.

Personally, I haven't found the recent crop of villain stories all that compelling. For an anti-hero, which is basically a person whose story we follow while certain they are morally bad, to be interesting to me they must be extremely and fascinatingly competent. Instead, most modern villain retelling seem to focus on filling in the psychological backstory, like why did he get that way, why does she want to kill the puppies, what's wrong with them? Honestly? I don't care. I'm not a forensic psychiatrist.

I don't want a hero who is an anodyne copy of a memory of Odysseus money-laundered through Joseph Campbell's bullshit totalizing heroes's journey theory. And I don't want its antinomian inversion either. Both are boring. I want to watch a problematic person be excellent at something.

Tina Turner sings "We Don't Need Another Hero."

Emily Wilson's introduction to her 2018 translation of The Odyssey by Homer, page 20. ↩︎

The problematic hero was Horn, the book was On Blue's Waters and the podcast is Alzabo Soup. ↩︎

Yes, I do mean chart. Some people might call it a table, which it also is. I'm personally convinced that a chart is the top level category and a table is a kind of chart when said table is the visual representation of data. I have really gotten into this, especially with other technical writers, some of whom are adamant that a table is not a type of chart but a totally different thing. And like, look, a table, when we talk about in the sense of a way to store data, is not a type of chart. But when you create an image of the data in tabular form so people can look at it, then it's a kind of chart. Various dictionaries, including for example Britannica agree with me: "information in the form of a table, diagram, etc." Maybe the more important caveat is that Aristotle probably didn't actually draw the table, and rather other people draw it based on his writing. I don't know; I haven't read Aristotle in Ancient Greek. Or if I did, it would have been just little snippets in college and I did not retain much. My advice to you is don't take two foreign languages at once. There are only so many grammatical particles a person can cram into their head at once, even at age twenty. At least I can still read the alphabet. ↩︎