It's a lovely morning in Moominvalley, and you are a horrible Snufkin. Except you're not really horrible, are you? And Moominvalley seems to be a bit less lovely than you had been expecting. What's going on?

What? #

If you don't know who Snufkin is or what the Moominvalley is, you're probably an American. In which case, the best explanation I can offer is by analogy to the comic strip series, Calvin and Hobbes. The feelings you have about Calvin and Hobbes, the way it captures the whimsy, melancholy, and unruly joy of childhood, the way it contains deep wisdom about the world that makes sense when you read it as a kid and then makes even more sense when you're an adult, the pure love and nostalgia you feel for it–that's how Europeans feel about the Tove Jansson's Moomintroll stories. I mean, I assume that it's the same. I actually don't have particularly strong feelings about Calvin and Hobbes and have been puzzled by how much adult Americans appear to love the comic strip for children which used to be published in newspapers, but just based on how they all act, I assume it is like the feelings I, and other people who grew up in Europe, feel about the Moomins.

Oh, did you think I was going to give you the full Moomintroll backstory. What? No. Why would I do that? You can still get the books out of the library. Or watch the adorable cartoons. Or not. I'm not your dad, or even your uncle. And maybe this only works if you are exposed to them at some formative age, like a little baby duck that imprints on the first thing it sees and follows it around[1], or like a boy who reads Calvin and Hobbes at the right age.

But the point is, for those of us who grew up with Moomins, "They made a video game where you play as Snufkin" is enough of a reason to check out the game. The vibe is right, which for me, was the most important thing. You don't actually need to know anything about Moomins to enjoy the game. However, without knowing what the entire, you know, thing, mood, gestalt, well, vibe is, you might not be as immediately drawn to it.

So while I'm not going to give you the Moomin backstory, I'll try to convey the vibe.

The setup #

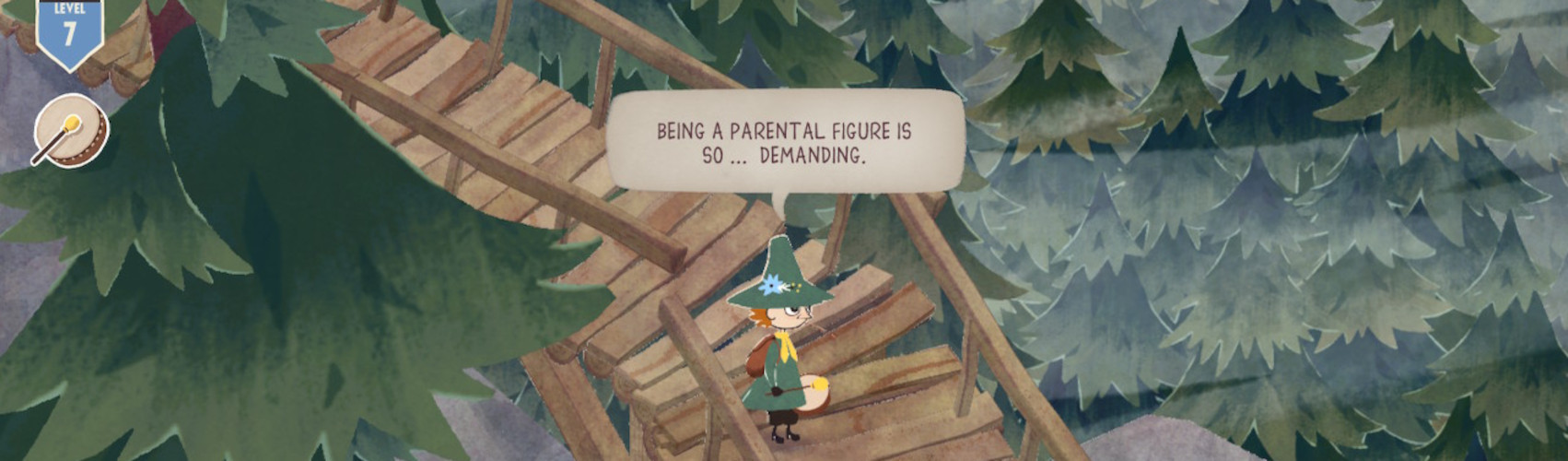

In the videogame Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley, you play the role of Snufkin, returning from his winter wanders[2] to rejoin his friends in Moominvalley for the summer. You walk through a beautiful forest rendered in the style of children's book drawings while atmospheric music plays. On your way to meet up with your best friend, Moomintroll, you start to notice signs that something is amiss in the valley. For one thing, there are all these signs all over the place!

Snufkin sees a sign forbidding pipe smoking. He is outraged that a sign should be placed in a wild place. This screenshot is from the Polish localization of the game. It's localized in multiple languages and I played it in both English and Polish.

It's a bad sign #

Snufkin is outraged, because–as you already know if you are familiar with Moomin stories, or as you quickly learn if you aren't–Snufkin hates rules. When you get close to the sign, an action button appears which lets you rip up the sign. Ripping up annoying signs becomes one of the major gameplay elements for the rest of the game, and it's incredibly satisfying. Destroying the signs with the rules written on them also destroys the power structure of laws and rules, which is a lovely wish-fulfillment fantasy. Rip up the signs, and the cops go away without a fight. Oh, and also the entire fenced and overly landscaped garden gets replaced with a wild meadow in a delightful victory sequence.

Snufkin rages while ripping up signs in the park. "Rules? Signs? This makes me so mad!"

All Conifers Are Beautiful #

As much as Snufkin hates rules, he loves nature and all wild things. He wants to be free and wild, and he wants other beings to be free and have a chance to be wild–whether those beings are animals or children who have been raised in an overly stifling atmosphere.

As Snufkin, you spend much of your time exploring beautiful natural environments–coniferous highlands, flowering valleys, mysterious caves, and the sort-of-tropical Hattifatteners' Island. Where these environments have been despoiled (and sorry, mild spoilers, they have been despoiled) through ill-considered development and attempts to bring order, you work to restore them. Along the way you help various people and creatures, including ones who might seem monstrous, and they help you.

Snufkin confronts some park police, with the fearsome Groke behind him.

Snufkin is willing to fuck shit up, and he enjoys a bit of chaos, but–at least as he is portrayed in the game–he is primarily motivated by his love of nature and his friends. He does not cause chaos for the pure unmitigated love of it. If Snufkin's vibe is ACAB, it's more like All Conifers Are Beautiful than All Cops Are Bastards.

That brings me to the other game whose protagonist is a freedom-loving individual driven to destroy the stifling constraints of bourgeois society. I kept thinking of that other game the whole time I played Snufkin, and of the ways the two of them represent different kinds of anarchist role models, or at least icons. Unlike Snufkin, that individual is driven by pure love of chaos with perhaps a touch of sheer malice. I speak of course of the goose from Untitled Goose Game[3].

And you are a terrible goose #

As the goose in Untitled Goose Game, you start out in a twee village full of boring, orderly people going about their day. An orderly village like that is perhaps what the Park Keeper attempting to gentrify Moominvalley wants to create instead of the half-wild Moominvalley with its eccentric and unruly inhabitants. In Moominvalley, the distinction between people and animals is blurry, whereas in Untitled Goose Game, it is clear. The goose is not really an outsider to the village, but it's definitely excluded from participating in public life. Peace, as Goose Game memes informed us, is not an option for the goose.

Playing the goose, you get to experience the joy of causing chaos for the sheer hell of it. The goose is a cypher with no dialogue and no discernable motivation other than just to destroy. And that's really fun! It also resonates with the impulse, or perhaps more accurately fantasy, to literally destroy an unjust world system, with no thought about what comes next.

The goose as an anarchist icon is most beautifully captured in a piece of fan art by Sarah Becan, where the anarchist slogan "No Gods, No Masters" frames a goose setting on fire a bunch of signs that ban geese. (Getting people to put up a sign like this is a reward for completing your quests in the Goose Game. You can also steal the signs.)

Goose fan art by Sarah Becan expresses the burn-it-all-down spirit many people feel the goose embodies. Prints and t-shirts are available on Sarah Becan's Threadless page.

Mutualist Snufkin, Egoist Goose #

Snufkin and the goose represent two different flavors of anarchism[4]. Snufkin seems very close to Kropotkin, valuing mutual aid, independence and interdependence, and a close connection between different species.

For example, when the cops guarding a park refuse to help him look for Moomintroll (because they are much more invested in guarding the commons they have appropriated as private property), Snufkin resolves to find Moomintroll himself. He looks for help from other people and creatures in the valley, and helps them out in turn, rather than relying on hierarchical authority. In the end, Snufkin brings all the people and creatures of Moominvalley together to restore Moominvalley and defeat the Park Keeper and his force of gentrifying goons. And he does so peacefully, using trickery, mild property destruction, and art. It's a kid's story version of mutual aid, which doesn't mean it's wrong. It's just a lot more simple and hopeful than these things usually turn out. Snufkin is a wholesome mutualist anarchist who loves nature, and a little mischief is (mostly) a means to an end.

Snufkin believes no one should be in a cage, and helps them escape.

The goose, on the other hand, is a straight-up egoist anarchist along the lines of Max Stirner's philosophical polemic, The Unique and Its Property (also known as The Ego and Its Own). The goose uses the power it has to secure the freedom it desires, defying social norms and honking contemptuously at bourgeoisie society. The goose doesn't get help from anyone and helps no one in return, terrorizing both adults and children with equal zeal. If the goose could speak, it would not surprise me if it quoted Max Stirner:

"You long for freedom? You fools! If you took power, then freedom would come of itself. See, one who has power stands above the law."

The goose shows no mercy to the weak. Screenshot from Untitled Goose Game courtesy of the official House House press kit.

But the goose can't speak and is not listened to, and being excluded, can only rebel. The goose is not nice. The goose is not a model, but a warning. Also, obviously, a fun power fantasy, as long as you can get a hang of the game controls.

Incongruity between form and content #

As a game, Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley, had some flaws that detract a bit from it. The first half or so of the game felt a lot more polished than the later portions. There were some glitches and performance issues when I played it on the Switch. There has been at least one patch since, so it's possible the glitches are fixed.

The biggest flaw, in my opinion, is the incongruity between the narrative message and the form of the game, especially, again, towards the end. The story is about restoring wildness and freedom from excessive order, but the form of the game is linear and structured. As Snufkin, you are led through a narrative about being unruly and free, but the narrative constrains what you can do and where you can go. That makes sense to me during the introductory sections which serve as a tutorial, but it's a little disappointing later on. You can't actually experience being unruly, except in specific narrative-driven ways. The constraints probably make the game easier to play. It's a relatively easy game, very forgiving with strong hints about what to do. It feels like something kids could play on their own, and that's good.

In the final chapter of the game, the puzzles become even simpler, and, due to a narrative event I don't wish to give away, you can no longer even use the sneaking and mischief-making abilities you've been practicing all along. The denouement of the game is a bit of a letdown, compared to the rest of it. It feels rushed, and I can't tell if that's because the development was actually rushed, or if the developers wanted to make sure that young players would not get stuck at the end. The player actions in the final section are very constrained, involve little skill, and don't feel like choices. The game really, really wants to make sure you see the amazing cutscene at the end, and it doesn't let you screw that up by making some wrong choices.

The conflict between guiding players through a specific narrative and giving players a sense of agency in the game is by no means unique to Snufkin, or even to video games[5]. However, because Snufkin's narrative is so strongly grounded in themes of freedom and agency, the irony sticks out. I think this conflict between form and content might hint at some ambivalence on the part of the designers towards Snufkin's anarchism. They show it, and they show it as a wholesome thing, but they aren't quite committed enough to it to figure out the daunting design challenges that they'd have to overcome to let you experience it as a player.

Conclusion #

Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley is a fucking absolute delight, and I would strongly recommend playing it. It is also (unlike my review) completely appropriate for children. If you're looking for a more traditional review that focuses on the gameplay, check out the Polygon review by Nicole Carpenter Snufkin: Melody of Moominvalley highlights Moomin's anti-authoritarian streak.

I don't think this is how ducklings, or any other birds, actually work. But songbirds do have only a certain window to learn the songs they will sing from adult birds, and if they don't, they never learn them. It seems that humans might work similarly when it comes to language acquisition. In any case, just take it as a half-baked analogy and not scientific fact, please. ↩︎

In the Polish translation, Snufkin's name is "Wloczykij" which means "wanderer." ↩︎

Untitled Goose Game by House House was released in 2019. See the Untitled Goose Game official website. ↩︎

There are of course many more than two kinds of anarchism, and perhaps there are as many kinds of anarchism as there are anarchists. ↩︎

Anyone who has ever attempted to DM a tabletop role-playing game has experienced the conflict between the illusion of choice players need to have fun and the narrative rails they need to stay on if they're to actually experience the cool campaign and dungeon map you've lovingly prepared for them ahead of time. ↩︎