Robot without rhyme or rhythm

ChatGPT and other LLMs can't write formal verse for the same reasons they can't do math

by

When I played with ChatGPT I tried to get it to write some poetry. I wasn’t sure how well it would handle writing creative material, but I thought it would probably be able to create formal verse. After all, it’s just following rules and machines are good at that. Right?

Your haiku suck and your sestinas are sub-par #

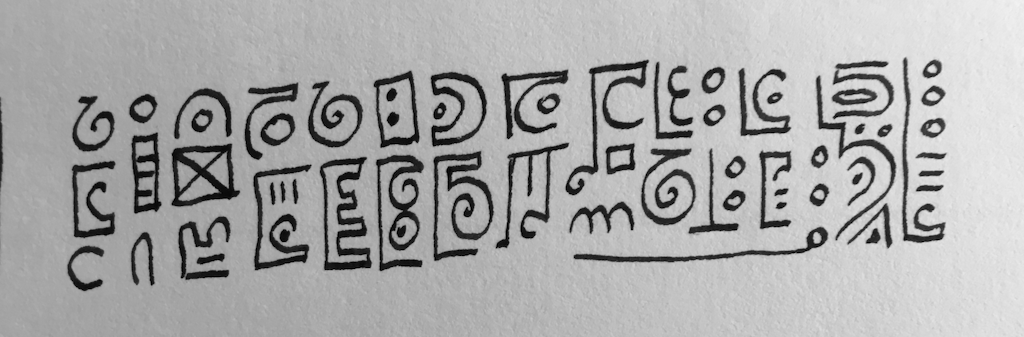

But it didn’t work like that at all. ChatGPT absolutely could not handle formal poetry. It sucked at rhyme, which after some reflection, I realized, fine, OK it doesn’t have the experience of words as sound. It sucked at rhythm. Fine, same idea. When I asked for a sestina, things got weird though. A sestina is made of six stanzas of six lines each followed by a three-line stanza. The most striking thing about a sestina is that it reuses the same six words at the end of each line, alternating in a particular order. That does not require the experience of words as sound.

Yet, ChatGPT, while able to define what a sestina is, never even attempted to reuse words at the end of each stanza. Worse yet, it always ended the sestina early, usually ending with a too-long stanza.

OK, maybe sestinas were too long for the bot, I thought, and I asked it to produce some haiku. At first, the haiku looked good. Haiku-shaped. Then I counted the syllables, looking for the 5-7-5 pattern and–nope! ChatGPT was producing the haiku equivalent of bullshit. Plausible enough if you didn’t pay too close attention.

So I decided to try a nonce form and asked ChatGPT to produce a poem with a particular number of stanzas and a set number of stanzas per line. Over and over, it would write a few stanzas with the correct number of lines and then veer off towards the end and produce a much longer stanza. Like it lost count.

The danged robot couldn’t count. The poems were also trite and verbose, so I soon lost interest in using ChatGPT as a writing toy. As a tool for exploring poetry, it was less exciting than cut-up technique or poetry fridge magnets.

“A superficial approximation of the real thing, but no more than that” #

In “ChatGPT is a Blurry JPEG of the Web,” Ted Chiang explained that when large language models (LLMs) are trained, they don’t actually assimilate the underlying principles. Instead, they produce the statistically likely next thing. (If you have some time, you should go read the essay. I’ll wait. Everything I have to say will make more sense afterwards.) He gives an example with arithmetic:

“Let’s go back to the example of arithmetic. If you ask GPT-3 (the large-language model that ChatGPT was built from) to add or subtract a pair of numbers, it almost always responds with the correct answer when the numbers have only two digits. But its accuracy worsens significantly with larger numbers, falling to ten per cent when the numbers have five digits. Most of the correct answers that GPT-3 gives are not found on the Web—there aren’t many Web pages that contain the text “245 + 821,” for example—so it’s not engaged in simple memorization. But, despite ingesting a vast amount of information, it hasn’t been able to derive the principles of arithmetic, either. A close examination of GPT-3’s incorrect answers suggests that it doesn’t carry the “1” when performing arithmetic. The Web certainly contains explanations of carrying the “1,” but GPT-3 isn’t able to incorporate those explanations. GPT-3’s statistical analysis of examples of arithmetic enables it to produce a superficial approximation of the real thing, but no more than that.”

That’s when it clicked. First, yes, ChatGPT couldn’t count lines or stanzas because it can’t really do arithmetic. It can produce statistically likely approximations of arithmetic operations, but asking it to count lines and stanzas in even a moderately complex way, especially in a novel form, asked it to apply the principles of arithmetic. And that’s just not now LLMs “learn.”

More than that, formal verse is an exercise in applying principles you’ve understood. ChatGPT could produce a statistically likely definition of a sestina based on all the examples of sestina definitions it had come across in its training. To produce a sestina, it would have to have assimilated the principles, and frankly, foiling the six repeated words through the stanzas and then correctly ordering them in the three-line envoi is complex enough that I’ve always had to chart it out to do it. It’s a little too much like carrying the “1” for an LLM bot (at least, as currently constituted) to manage. You can’t bullshit your way through a sestina.

Thinking about formal verse as an application of internalized principles, as opposed to an LLMs' statistically likely approximation also explains the strange haiku. They were a superficial approximation of haiku-shaped objects, a blurry-JPEG of a real haiku which only appeared at a passing glance to meet the criteria.

The violence of the letter #

There’s one more reason why LLMs can’t write formal verse, and this one is a little more obvious, though still, I think, worth mentioning. LLMs are trained exclusively on written text. They do not have the sound of words in their training, as far as I know. I am careful not to write that LLMs don’t have the experience of the sound of words, because they don’t have the experience of anything. And anyway, I don’t want to get into p-zombies right now. I want to keep it technical.

Formal verse with meter and rhyme relies on the sound of the words. While you can guess what words are statistically likely to rhyme based on their spelling, it’s only saying them out loud that lets you know if you’ve succeeded. Theoretically, a model could be programmed with the contents of a rhyming dictionary, but I suspect we’d once again run into the problem of being able to apply internalized principles when actually using those rhymes in a poem.

Meter is even more tricky. You can look up words in a dictionary to find out which syllables are normally stressed, but sometimes the stress varies depending on the words around it. You can only really be sure of it if you say it out loud.

Ever since writing became a thing, people have used writing to talk about how dangerous writing is, how unnatural compared to speech. Derrida has a whole thing in Of Grammatology about how dangerous and unmoored the written word without sound is seen to be. You can go read Derrida if you’re a big nerd, but I wouldn’t suggest taking a break from my post to read him. You’d be gone for months.

Maybe seeing ChatGPT will make some new people reflect on the violence of the letter unmoored from human speech.

Envoi #

There are a few more things I want to touch on, but it’s late and I want to finish this post, so I’ll just kind of list them without developing them much.

First, thinking about the way that machine-generated content has swamped the slush pile of Clarkesworld magazine, I wonder what other effects LLMs will have on literature. Might formal verse in English, which has fallen out of favor since the early 20th century, make a comeback as a prestige form, edging out free verse?

Second, I wonder if LLMs could write decent free verse, anyway. Poetry relies on deliberately pushing the rules of language in creative ways and putting together fresh combinations of words in statistically unlikely combinations.

Finally, I wonder if, given that LLMs can produce polished but contentless prose corporate speak, will poetry make a comeback as the form for signaling sincerity? Could you imagine getting a notice of layoffs from your very humane VP in the form of sonnet? I’m not sure it would be a better world but it would be interesting.